Shalinee Kumari (She/Her) Editorial Assistant, The Third Pole Shalinee Kumari (She/Her) Editorial Assistant, The Third Pole Shalinee Kumari is an editorial assistant at The Third Pole. Prior to this role, she worked as a trainee digital journalist with BBC Hindi. She is a postgraduate in Convergent Journalism from AJK MCRC, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. During her post-graduation, she also worked as an independent journalist covering the environment. She can be reached on X here and on Instagram here. You can also follow The Third Pole on X, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn. With rising temperatures and its impact on lives and livelihoods becoming increasingly apparent, the need for clear communication on climate change has never been more urgent. This communication also needs the active engagement of communities affected by climate change. Those who suffer the most are often vulnerable and low-income groups. However, these communities are often left excluded from these important conversations because of the barrier created by technical language used in climate communication. In my experience during field trips, I observed that there is a clear language gap between how climate impacts are explained in media reports and what is being perceived by the communities worst affected by these impacts. This is also a common experience shared by many journalists covering the environment and climate change. Since conversations on climate change are often dominated by jargon, it creates an obstacle to understanding the true impacts of the changing climate for local communities who are not familiar with the terms used in policy and science spaces. Hence, there is an increasing need to have conversations on climate change in not just the policy and media spheres but also in the public sphere in a way that can include more and more people in the decision-making. To help facilitate such conversations, The Third Pole has introduced a comprehensive list of terms related to climate change with brief definitions and clear explanations. To make these conversations more inclusive, we have this climate change glossary available in Hindi, Urdu, Bengali and Nepali, some of the languages spoken in the Himalayan watershed. The key to contributing to conversations on climate change is to have a solid understanding of what is happening to the environment. This will help people make informed choices. Another observation in regional climate storytelling is that some of the technical words used in the English language are not easily translated into regional languages. Some of the translated terms are as difficult to understand as their English equivalents because these technical terms are not used in everyday conversations. Hence, there is an urgent need that communities get familiar with the terms so that they can be widely accepted and understood. Referring to this glossary will also help journalists with climate storytelling. What can make climate storytelling better is to simplify and humanise the coverage. This glossary can be a useful guide for journalists who are new to climate storytelling as this could not just be a guide explaining terms to them but also a resource that can help them with new ideas. One way to use this could be to go through the terms and see which key term lacks media coverage in their particular region and ideate new angles to cover that. Which terms can be turned into explainers (like GLOFs or CCUS)? Can we do a ground report on a topic (like Just Transition)? Another way could be to use these definitions in their reportage as a quick reference (like a pull-out box quickly explaining Tipping Point.)

We are aiming to make this a dynamic list of terms, meaning that we will keep adding new terms to the glossary as and when there comes a need to explain a new term. We would love to hear from the readers of the glossary on how they feel about it and if there are terms we should consider adding.

3 Comments

Despite popular belief, the city of Buffalo is not always encased in a thick blanket of ice and snow. While winter weather certainly takes an unfortunate liking to the western New York city, its residents are often rewarded with a handful of glorious summer weeks. Having grown up on a farm outside of Buffalo, I am all too familiar with the sweltering heat of a Buffalo summer. I recall waking up early for summer camp, when the grass in the yard would be damp with dew. The cicadas would still be sleeping and the sun would just barely coat the farmland with rays of honey. Summer mornings on my childhood farm felt nearly religious. When asked where my passion for environmentalism came from, I point to that place in all its nurturing glory.

When I wasn’t filling the days of my youth with adventures in The Great Outdoors (the cornfields of the backyard), I was likely writing short stories at the kitchen table. I have always loved writing nearly as much as I have loved nature. Thus, when I discovered Climate Stories Project it felt serendipitous. It was an opportunity for me to combine two of the greatest joys in my life- storytelling and environmentalism.

Climate Stories Project has revealed to me how powerful storytelling can be as a tool to combat the climate crisis. Throughout history, oral storytelling has been the primary medium by which lessons from our natural world have been shared. From Native American legends to African folktales to Celtic myths, oral storytelling about the environment has been passed down through generations across the globe. If storytelling can be used to preserve and share the wisdom of our earth, why not use storytelling to also protect and defend it?

Initially, I embarked on my environmental storytelling journey with the goal of connecting more with our earth. Yet along the way I realized that it has also connected me more with humanity. Whether I was listening to the stories of other Climate Stories Ambassadors or speaking with people in my own community about climate change, I have felt threads of interconnectedness weave themselves between me and those I interact with. In reflecting upon this, I find that connecting with humankind is a part of connecting with our greater earth. For humans are just as much a part of nature as the trees and flowers and animals. We are all the same in that we are sustained by the planet we find ourselves on. There is something beautifully comforting about that.

While I still have much to learn about environmental storytelling, I am grateful for all that Climate Stories Project has already taught me. It has given me a place to learn, reflect, and grow in climate advocacy. Above all else though, it has instilled in me the power of listening. For true change cannot take place until we understand what we are up against, which can only be done by listening to the stories of those we share this earth with. By Jason Davis, director of Climate Stories ProjectMay is the height of seasonal drama in Massachusetts, where I make my home. The Earth thrums with a sensory overload of surging life: otherworldly pink and white blossoms erupt from magnolia trees, electric orange and black Baltimore orioles flash overhead, and mosses glow vibrant green after spring rains. I am especially attuned to the riotous soundscapes. The first-of-the-season “ee-o-lay..” of a wood thrush, or the ethereal chirping of spring peepers at dusk are quintessential sounds of the New England spring. Wood thrush image by Vinson Tan. Wood Thrush recording by Imonacan, shared under Creative Commons licenses. Despite my delight in these auditory riches, I worry that listening carefully to the sounds of the Earth, and to each other, is becoming an endangered practice. I admit that I cringe when I see someone hiking through the woods yammering into their phone or plugging their ears with ear buds. I long to shake these folks: ditch the devices and listen! The world outdoors is so much richer than a tiny smartphone screen. What are we to do? For an antidote to this crisis of inattention, we can turn to the listening practices of Indigenous cultures from around the world. Place-centered cultures universally value attunement to the sounds of the environment and to the speech of others, honed from generational knowledge of living in an intimate relationship to the land and to community. You can scarcely afford to block off your hearing with headphones when your survival depends on focused attention to the sounds of animal movement, wind direction, and running water. Similarly, place-based cultures rely on the words and wisdom of elders and oral traditions for survival and connection. An example of this elevated approach to listening is the Aboriginal Australian practice of Dadirri: a means of listening intently to the sounds of the Earth and to each other with reverence, patience, and respect. Elder Dr. Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr from Nauiyu (Daly River) describes Dadirri: In our Aboriginal way, we learnt to listen from our earliest days. We could not live good and useful lives unless we listened. This was the normal way for us to learn—not by asking questions. We learnt by watching and listening, waiting and then acting. How unlike our hyperactive communication style, in which listening plays a distant second to speaking. Like most of us, I find it challenging to focus on the words, the tone, and to the cadence of someone’s speech without planning my next verbal move. However, when I manage to let go of this strategizing and just listen, I can feel the other person relax, even over a phone or Zoom call. Then we have a chance for a real connection, rather than a just having a “transactional” conversation. What does this have to with climate storytelling? Climate change is transforming the voice of the Earth. Many studies have documented steep declines in the diversity of insect and bird sounds over the past 30 years. But you don’t have to be a scientist to be aware of how soundscapes are changing with the climate. One of the most memorable stories I have heard was told by Inupiat elder John Sinnok from the frontline climate change community of Shishmaref, Alaska. I spoke with John in September, 2015 during a series of climate storytelling workshops I led with local high school students. At the end of our conversation, John mentioned that the sound of people walking through the snow has changed as the climate has warmed and the snow has become wetter. This sonic detail deeply moved me, and I wrote and recorded a music piece called Footsteps in Snow which features John’s words. The more I ask people to share their climate stories, the more I realize that storytelling should really be called story listening. Listening is the key to empathy and respect, qualities which are sorely needed these days to successfully confront the climate crisis. I cannot put this better than Henry David Thoreau, who wrote: The greatest compliment that was ever paid me was when one asked me what I thought, and attended to my answer.

This post is by Climate Stories Project Program Manager Kelly Hydrick. Climate change today is often considered from the point of view of the physical sciences and numerical data, but this data can often be difficult to connect to our daily lives. Unless we or people we know have experienced adverse climate change events then reports of shrinking sea ice, rising air pollution levels, or habitat loss might be easily dismissed. In my work for Climate Stories Project I have conducted numerous oral history interviews about people’s experiences and reflections on the Earth’s changing climate. I’ve asked my narrators to really think about climate change and how it connects to their daily lives, something that many of them had never done before. Although climate change can be difficult to think about, let alone discuss, storytelling can help bridge the disconnect between abstract scientific concepts and our lived experiences. With this in mind, I created the digital story, Climate Change Interviews: 2020. By combining excerpts from three interviews with music and imagery I created a story which reflects on the process of conducting climate change oral history. Storytelling is an important communication tool, especially when it comes to addressing difficult topics like climate change. From our earliest oral traditions, filled with tales of epic journeys, love, and loss, as a species we have developed an affinity for narrative. People love to listen to and tell stories in order to imagine, explain, and share. We use stories to connect with each other and the wider world and this is no less true today than it was millennia ago. Stories about the natural world have featured prominently in various storytelling traditions because for so much of our history humanity has lived in close proximity to nature. Examples can be found in tales of a great deluge in Gilgamesh and the Old Testament, in the weather in Shakespeare’s writings, and in poetry about the seasons from across the globe. Although it might not be as readily apparent as in the past, our modern lives and the natural world are still interconnected. In the twenty-first century, given our rapidly changing global climate, we have important new stories to tell about nature and the environment: about devastating droughts and wildfires, record-breaking floods that occur with startling regularity, or quieter changes like the disappearance of wildlife. From the beginning, the art of storytelling has continually changed along with our tastes and technologies. Today, in addition to oral, written, and visual storytelling, digital storytelling has become a popular narrative technique. Similar to filmmaking, digital stories combine a variety of media elements such as audio, video, text, and still images, in addition to social media and other interactive features. The near ubiquity of mobile phone cameras, free audio and video editing apps, and open source media files, along with online video-sharing platforms have given more people than ever the chance to tell their stories. To find the narrators for my digital story, I contacted friends and acquaintances via social media and explained the interview process and how it fit into the larger Climate Stories Project to change the ways we communicate about our changing climate. Before I ever sat down to talk with my narrators I did a lot of preplanning to make sure I was up-to-date on climate issues as well as best practices for conducting oral history interviews. I also created a list of about ten questions to ask but made sure to leave room for improvisation as well. After editing the interviews, I began planning the digital story itself. Visually, I wanted to reflect what my narrators discussed as well as remind viewers of the beauty and diversity of life on Earth and why we should all care about climate issues. The majority of images I used are from my own personal collection and I supplemented these with photos provided by my narrators, imagery from global news agencies, and from the Creative Commons. The music tracks and an excerpt from Carl Sagan’s “The Pale Blue Dot” completed the story. For me, creating this digital story was an emotionally powerful process and a distillation of months worth of work. Stories we tell about the Earth’s changing climate affect how we think about and ultimately respond to the myriad challenges we face. The scientific data about climate change have been well-known for decades - what’s needed now are ways to highlight the connections between the science and our day-to-day experiences. I hope Climate Change Interviews: 2020 helps make this connection more apparent so that, in the words of Carl Sagan, we might learn “to deal more kindly with one another and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”

This blog post is by Jason Davis, director of Climate Stories Project.In the 2018 Yale Study Climate Change and the American Mind, researchers found that only 6% of Americans believe that we can and will take the needed actions to prevent the climate crisis. This finding is, to say the least, discouraging. We can’t confront climate change without a vision for a better future, or for reimagining our relationship with the biosphere. Without question, urgent action is needed—we are decades behind schedule in tackling climate change. In May 2020, global atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide reached 417 parts per million, continuing an inexorable upward trajectory despite a brief dip caused by worldwide Covid-19 shutdowns. Those of us paying attention are understandably terrified that nothing resembling an adequate response to this crisis is even on the table. However, we should take a step back to examine what it means to “take the needed actions” to prevent the climate crisis. There is no silver bullet. Climate action can take many forms, such as trading a gas guzzler for a Prius, voting for responsible elected officials, taking part in a climate protest, installing solar panels on your roof, or a national government following through with promised greenhouse gas emission reductions. Taking action on climate change also means community adaptation: building sea walls, planting drought-resistant crops, or improving emergency services in front-line communities. Sometimes climate action is action in the most drastic sense: forced migration, or community abandonment because of drought or rising seas. Is sharing our climate stories a form of action? We may think that climate action only means doing things—making concrete changes in the outer world—but effective climate communication, and climate storytelling, is required for the needed realignment in how we relate to each other and the climate crisis. Furthermore, talking and listening about climate change creates the needed space to make effective decisions about what action means for individuals, communities, and governments. Climate action can also be inner action to come to terms with our own climate stories. In her 2019 book Welcoming the Unwelcome, American Buddhist nun Pema Chödrön emphasizes the need to embrace painful truths, whether on a personal or societal level, before effective action can be taken. She argues that if we want to be activists, we need to face our own inner challenges and our own pain so we can engage in action with a clear head. In this sense, any form of successful outward action to confront climate change is balanced by inner acceptance and wisdom, which can be fostered by climate storytelling. Climate storytelling also makes climate change “real.” Research has shown that a significant barrier for greater societal engagement with climate change is that many people do not relate to climate change as an issue that affects them personally. One of the most effective strategies to developing greater engagement with climate change is recognizing how the crisis threatens personal “objects of care” such as National Parks, local agriculture, vibrant communities, or more abstract objects such as future generations or animal species. articulating and communicating our emotional connections with these “objects” gives rise to a deeper commitment to take part in meaningful action to confront climate change.

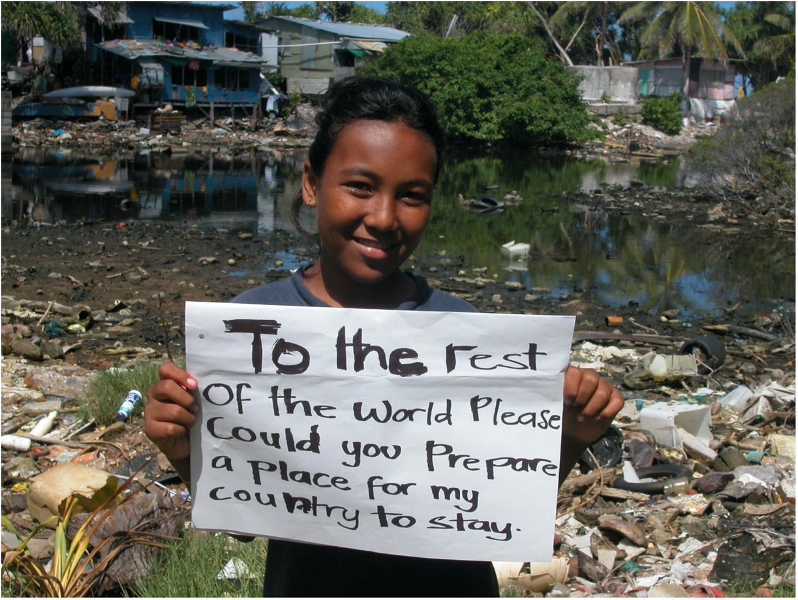

In short, climate storytelling is a right-sized, approachable, and gratifying action for many people. While it doesn’t negate the need for political organizing, climate storytelling is accessible to anyone regardless of age or geographic location. And unlike lifestyle changes, storytelling directly connects us to our neighbors and wider community while moving us away from the individualist, consumer mindset that is a prime driver for the climate crisis. With this understanding, encouraging friends and family to connect with their objects of care through climate storytelling is one of the most effective actions we can take. This blog post is by Climate Stories Ambassador Kelly Hydrick: My name is Kelly Hydrick and I live in Worcester, Massachusetts with my family. I am a trained historian, although before volunteering as a Climate Ambassador I had no formal instruction in oral history. Currently I’m back in school, in my first semester of a library and information science degree program. One day, I hope to combine my library studies with climate change communication, although I’m not exactly sure yet what this synthesis could look like. As you might imagine, I love to read, and in fact it was my love of reading which first prompted me to delve deeper into issues surrounding global climate change. In the summer of 2019 I read The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable by Amitav Ghosh (2016), a book about the lack of climate change representation in modern fiction. The way Ghosh seamlessly integrates literature, history, and politics in order to examine climate change left a lasting impression on me and inspired me to write a lengthy essay on the issue. After months of research and writing I published a three-part article about how representation of climate change in fiction writing is improving. During my research I started to recognize the disconnect that exists between the different types of climate change communication to which people are exposed. This disconnect between science and history, policy and literature, the global and the personal, affects how (or even if) we think and talk about climate change in our daily lives. When the interconnectedness of climate change is obscured we miss opportunities to make meaningful choices about how to engage with the challenges of a warming planet. Working as a Climate Ambassador As a Climate Stories Ambassador, I was able to interact with people from all over the world who are just as passionate as I am about dealing with climate change and it gives me a great deal of hope, seeing the interest that is out there. Part of what drew me to volunteer is that Climate Stories Project is attempting to change the ways we communicate about climate change. By conducting oral histories, by talking with each other, we are humanizing and personalizing an issue that affects us all. Conducting the oral history interviews provides hope as well. There are common themes that became apparent in the interviews: concerns for the future world in which our children will live, food security, and climate refugees, as well as the hopefulness in things people do everyday to make a difference, in the passion of young people to affect positive change. The interviews I have conducted have highlighted that people are aware of climate change and they want to do something about it. They want to help, but the ways in which climate change is communicated by the media so often makes the issue seem too big, too far in the future, too hard, too much to deal with. So much of this experience as a Climate Stories Ambassador and as an oral historian, has made me realise that it is not about me. It is not about a single person or even a single group of people. Climate change is about everyone on the planet. Conducting climate change interviews with people from your community will allow the world to hear from ordinary people who aren’t politically powerful, who don’t have unlimited resources, and who will, in one way or another, be affected by climate change. One of the questions that I’ve asked at the end of every interview I’ve conducted is: “If you could talk to the person who is listening to this oral history recording thirty or forty years from now, what would you tell them? What message would you want someone in the future to know about climate change in 2020?” Each time I asked this question I got goosebumps hearing people’s answers. There was just so much pain and so much hope in the responses. I would like anyone listening to these climate change stories to hear the pain and the hope, and to realize that so many people today do care, deeply, about climate change.  This post is by Shilpita Mathews, a Research Assistant at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment who frequently writes about climate justice on her personal blog. Having witnessed the aftermath of the Asian tsunami in 2004, I’ve been struck from a young age by how devastating natural disasters can be. Unfortunately, such natural disasters are becoming far too common an experience for today’s youth as a result of climate change. Growing up in India, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Jordan, I was always aware that climate justice is intrinsically linked to social justice. Whether it be extreme weather events or water and food shortages, climate impacts are disproportionately borne by the most marginalised in society. The role of climate change in exacerbating inequalities beckoned me to respond. I've been trying to grapple with these challenges as a Research Assistant at a climate change institute whilst completing a postgraduate degree in environmental economics and climate change. Moreover, I shed light on the social repercussions of climate change as a Climate Correspondent for an Indian youth news network. Most recently, having been part of a group launching a climate network for young Christians, I am encouraging faith communities to act as catalysts for change. Nonetheless, amidst the intellectual rigour, the journalist endeavours and social activism, it is easy to forget the reason behind it all – a personal climate story. A story of a life journeying alongside climate change. I have been drawn back to not just my story, but the story of every single person on this planet. Connecting with people behind these stories has the power to evoke a response, much stronger than any research, news or campaign can elicit. As a young professional, currently emerging from lockdown in London, I often feel distant from the vivid realities that I grew up with. Despite the tremendous challenges that climate change poses for the UK, which is the topic of my current work, I keep going back to the stories in countries I call home. To this end, I have been using my creativity, to fill the void between myself and those adapting to climate change around the world. Connecting with people who I may have never met, but whose visual narratives I have taken the liberty to give a voice to, in less than 100 words. I call these stories Climactic Tales, which you can find on my blog. Using Creative Commons photos, I present four short narratives here, piecing together stories of hope and despair that define the global climate emergency. Perhaps they remind you of someone, or of a reality that you too, find easy to forget. A reality that is so distant yet so present, a story that is within us all. Perhaps they remind you of home, a common home that is under threat. I hope these stories invite you to engage with climate personally and present a chance to reflect on your own climate journeys. New Normal In the midst of the storm, the food hawkers gawked, as their drenched customers for the day whizzed past their sight. From behind the pharmacy counter, a man sneered at the filthy flooded road, gazing at the breeding disease. Caught up in the hammering rain, their old motorbike and soaked face masks were inadequate for the torrential journey back home. Flood. Food. Disease. One less meal, one new illness, one more day in this new normal. Boat of redemption A rotten garland, a dead fish, a plastic bag, in the middle of a Holy river he stayed afloat; drifting on top of the sins of the world. A stinking carton, a torn rag, some styrofoam. With the waste that built the lives of the rich, had he built his new sanctuary. Could this waste lead to the path of redemption? Could his recycling, his karma today, be reaped by the generation to come? He paddled with his makeshift oar – it was time to change To the rest of the world To the rest of the world, please could you prepare a place for my country to stay. Could you find a home where my future is safe? Could you rejuvenate the planet, not for me, but for us. Could you bring back the nature you have turned to dust. Could you bring back the birds that used to sing? Could you restore fresh water to drink? To the rest of the world, could you finally wake up. Could you realize, alas, our time is up. The disentanglement One by one I disentangled them. The wires of waste, the want for more. Minute but minute, hour by hour, piling up that which belongs to a degrading planet. Scraps of another existence, a world living beyond its means. Yet the chiming dime in my pocket makes me think, perhaps we will return from this brink. Perhaps these are chords of new beginnings. Perhaps recycling will help disentangle some of the chaos we have created. Source of life The solar pump operator finished his work. The energy that flowed through farmers’ irrigated fields at day, radiated in homes, where children completed their homework at night. He gazed in the distance, wondering whether the light that filled his village would ever illuminate dark, polluted human hearts. In finding ways to save ourselves, would we turn to the source of life?

By Jason Davis, Director of Climate Stories Project During the past several months, many people have written extensively about the connections between the devastating Covid-19 pandemic and the climate crisis. The remarkable similarities between the twin emergencies include the dynamics of denial and delay, the false tradeoff between public and planetary health and the economy, the unveiling of profound societal inequities, and the pressing need for social trust and governmental action in finding solutions. However, while the climate crisis is evolving over years, the pandemic is unfolding day-by-day. It is safe to say that those of us engaged with climate change are disoriented by the turn of events. I had a sense for the rough contour of the next decade: without drastic change, CO2 will continue to be emitted, seas will rise, crops will wither, and societal bonds will fray. Given the suddenness and severity of the Covid-19 pandemic, nearly everyone on Earth has a personal “virus story,” ranging from the tragic death of family members and severe health impacts to a gnawing sense that the world as we know it has changed, possibly forever. It’s clear that severe societal, public health, and economic disruption can come from unexpended quarters and the veneer between business as usual in developed countries and disruption and confusion is razor thin. Lately, I’ve started asking people to speak about the connections between their virus story and their climate story. Reflecting on the pandemic, interviewees recount how their sense of normalcy and familiar routines fell away, seemingly secure employment evaporated, and close personal relationships were forced online. The pandemic is adding urgency to the need to share stories that bind us together in collective responses to global threats. Can we tap into our intimate stories about the pandemic to access our climate stories? Like virus stories, climate stories reflect vast inequities in degree of threat, exposure to risk, and available resources to adapt to climate impacts. Some people, such as members of Inuit coastal villages and residents of low-lying islands, are facing imminent dislocation from their homelands, while some those of us fortunate who live in relatively developed countries may be observing subtle seasonal shifts and anxiously anticipating future disruption and dislocation. Perhaps this pandemic has opened our perception into the dark shadows of societal climate grief, making it easier to access our concern for planetary health and our raw feelings around climate disruption. While deeply confusing and painful, this crisis presents a valuable opportunity to reorient our relationship to public and environmental health, and to connect with people from around the world around pressing threats to health and livelihoods. It is imperative that we seize this moment to push for deeper engagement with each other as we seek a meaningful way forward through both the immediate pandemic and the long emergency of climate change.

By Jason Davis, Director of Climate Stories Project Recently, I rode my bicycle along the Norwottuck Rail Trail, a former railroad bed turned bike path, which links the towns of Northampton and Amherst, Massachusetts. Riding on the trail in early February felt weird: I had put my bike away for the season in December, despondent at the thought that I’d have to wait until spring to ride again, when the snow and ice would be gone. But here I was, zipping along ice-free pavement in what should be the coldest part of the year. Joggers passed by in shorts and t-shirts. Suddenly, a likely startled Cooper’s hawk (or maybe a Sharp-shinned hawk) swooped down and flew in front of me, directly at eye level. During those 5 seconds that I was trailing the hawk on my bike, I felt a bizarre sensation—my legs pushing the pedals became like wings moving up and down in tandem with the hawk’s. What delight!  Cooper's Hawk: licensed under Creative Commons Cooper's Hawk: licensed under Creative Commons Briefly commingling with the Cooper’s hawk lifted me from my unease with the unseasonable warmth. While part of me was enjoying the spring-like weather, I long for it to get cold, below-freezing cold, in December, and stay that way until March. I remember childhood days walking out onto Walden Pond in late January, my breath coming out in clouds, snot freezing in my nose, and marveling at the glassy solidity below my feet. Small bubbles and cracks were suspended in the ice, above the inky darkness of the lake. It was winter, cold and unapologetic. In Henry David Thoreau’s 1854 book Walden; or Life in the Woods, he writes: “On the 13th of March, after I had heard the bluebird, song-sparrow, and red-wing, the ice was still nearly a foot thick.” How would he respond to an unfrozen Walden Pond in February? Like Thoreau, I imagine, my first love affair was with the seasons of New England. There is high drama in the turn of the year in this corner of the world—barreling thunderstorms sweeping away the stagnant late-August air, the first tendrils of frost appearing on the grass in October, the play of weak sunlight during short December afternoons, the riot of new life bursting forth in mid-April. Composer Igor Stravinsky describes the genesis for his masterpiece the Rite of Spring as “the violent Russian spring that seemed to begin in an hour and was like the whole earth cracking.” The New England spring may be somewhat less violent, but no less dramatic. Much of this seasonal drama comes from anticipation of changes to come. Thoreau understood this sentiment intimately: In his journal entry of March 8, 1853 he wrote: “At the end of winter, there is a season in which we are daily expecting spring, and finally a day when it arrives.” How would Thoreau expectantly anticipate the thaw of spring with no snow or ice in February? So much of the worry about climate change is about well-justified fear of threats to livelihoods, health, and property— ruined sea ice, failing crops, flooded neighborhoods. These are vitally important concerns, but what about the impact of fractured seasons on our psyches? How can we orient ourselves in a world where the seasons can no longer be counted on as a source of emotional sustenance and stability? Maybe younger generations don’t share my nostalgic attachment to the muscular seasons of my childhood, but I can’t imagine that they don’t feel a creeping anxiety wrought by such a rapid disruption of familiar seasonal patterns. A question looms low on the horizon like an August thunderhead: How do we find our center in seasonal cycles that we can’t count on anymore? Right now, I don’t know the answer to that question. However, I know that joy is still possible in our fast-changing world, even if it lasts 5 seconds biking in the windstream of a Cooper’s hawk.

This blogpost is from Worcester Polytechnic Institute Global Studies professor Ingrid Shockey. A group of her students visited Himachal Pradesh, India in spring 2019 and recorded climate stories from residents there. Bringing STEM Students into Climate Change Conversation Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) is known for science and engineering education, but a key aspect of its curriculum asks all third-year students to participate in a project-based learning experience on a topic at the intersection of environment, technology, and society. As a global studies professor, I have the unique opportunity to facilitate students through this process. Most of my students arrive in my class already globally-minded and committed to making a contribution with their careers. They are motivated and interested, but they lack critical skills and the confidence for engaging in and with real communities. STEM students are well-equipped to design technological strategies to mitigate climate change, but there is a significant gap between theory and learning first-hand from individuals in vulnerable locations. In 2017, I embarked on a challenge to teach students how to collect climate change stories from lifelong residents in rural and urban communities in settings away from the university. I work with small teams of students each year at one of WPI’s off-campus project centers, most recently at a collaborative site in rural northern India. This environment is usually the first opportunity my students have had to interact with a community as part of their education, and for some it is the first time they have left Massachusetts. I can see that they are shy, and at first resist reaching out to strangers to initiate the conversations that will bring stories to life on camera. Many students are also new to creative media or filmmaking beyond social media posting, and struggle with equipment failures. Furthermore, they begin to learn—on the ground—that there are important responsibilities associated with storytelling. We discuss accountability in listening, we practice participation in difficult conversations, we reflect on our assumptions, and we weigh how media exposure might amplify our findings. WPI students tell me before these exposures that the weight of climate change and a future filled with uncertainty has left them paralyzed. The recording process prompts a cautious step towards activism. They know that the work of gathering scientific data and statistics is useful for informing models and government policy, but when students hear the experiences of ordinary people, it adds gravity to their understanding of how the changing climate is playing out in real life. As one student told me: Till now, I only heard about the statistics around climate change, but this project personalized the issue. We could hear the helplessness. We thought people were unaware, but they are not. They just don’t know what to do. Others have reflected on aspects of privilege, class, and power that cannot be felt in the classroom: We learned how livelihoods are affected, that people had to change how they LIVE. Our privilege right now is that we are not affected at this level yet. It made a change in me, in part of my life. We better understand the “human-wide” community that we are all together in this. To date, my WPI teams have recorded stories in Wellington New Zealand, in Iceland, and in northern India. The project center in India is further enriched by our partnership with third-year STEM students from the Indian Institute of Technology Mandi, where we curate an Instagram account together with images and short excerpts from the stories of rural villagers (https://www.instagram.com/messagesfrommandi/). The effort will continue onward to Japan, U.K., and Greece in 2020. I see important patterns in the full body of work. Some climate change indicators have emerged as a result of our citizen-science that are still not well-documented by local governmental agencies at the sites. In Iceland, the sub-Arctic landscape prompts memories about now-receding glaciers, anxiety about climate migration, and uncommonly heard phenomena such as land RISE and glacial surge related flooding. In rural Himalayan villages, residents wonder how and when the government will help them. Other findings confirm universal fears for global health and wellbeing that are shared by individuals, whether from Himachal Pradesh India, or Reykjavik Iceland: the outlook for families, futures, and livelihoods. All are glad to share their experiences. In the end, I am acutely aware that the simple process of listening and telling stories opens an exchange across culture, age, language, and space. My students will graduate as engineers and scientists having learned that even their short conversations have transformed how they think about the design of technologies and have contributed to a common vision for a desirable future. They are also humbled to learn that many of those most affected by climate change have never been asked to share evidence and ideas that are critical to the solutions. I find that the simplest path forward is to teach the art of empathy. Participation and practice in HOW to listen is the first step in linking environment, science, policy, technology, and sustainable futures. Ingrid Shockey ([email protected]) is an Associate Teaching Professor in the Interdisciplinary and Global Studies Division (IGSD) at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Her work focuses on teaching cross-cultural perspective-taking and fostering community engagement skills for teams. Aside from advising fieldwork with students, she directs two undergraduate Project Centers: a stand-alone site in Wellington, NZ (since 2012) and a partnered site in northern India at the Indian Institute of Technology at Mandi (since 2013). With a background in Environmental Sociology, she also teaches a course on environmental innovation and design for Environmental Studies at WPI. Most recently, she was the inaugural Global Fellow in residence at the Global Lab in the Foisie Innovation Studio at WPI, working on a project to map climate change stories.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed