|

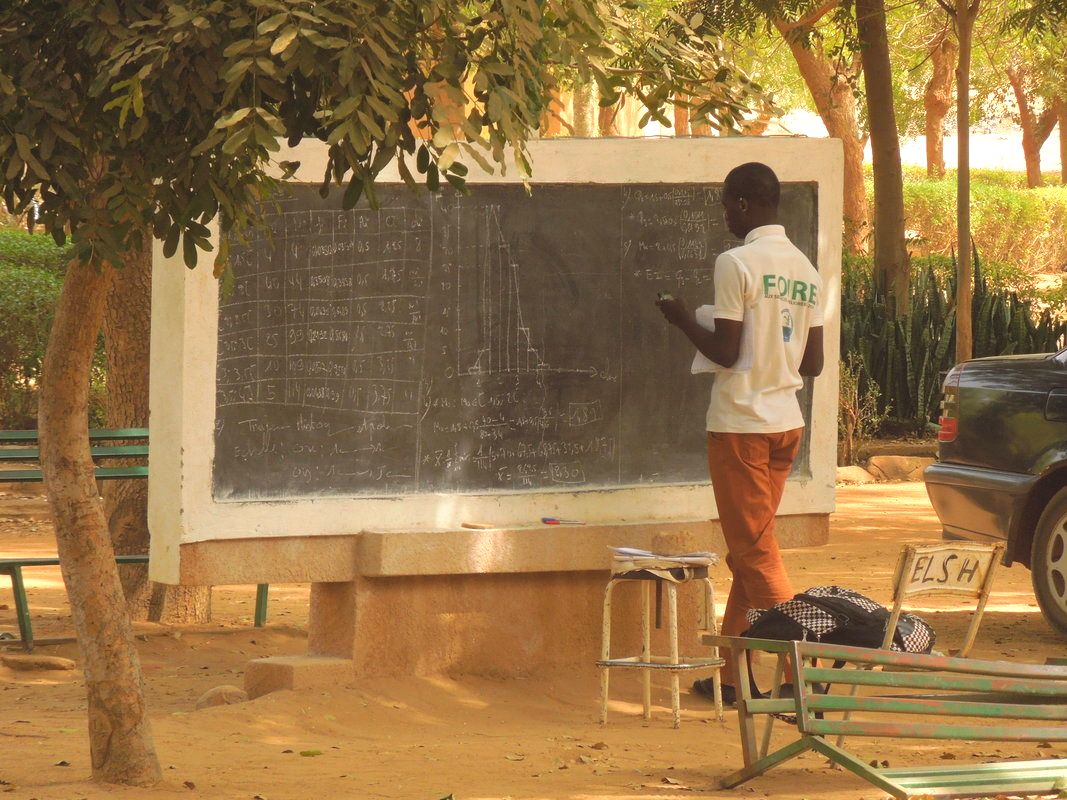

In this post, geography professor Sara Beth Keough of Saginaw Valley State University describes her work with West African graduate students in Niamey, Niger. During her time there as a Fulbright Scholar, she coached the students in planning and recording their stories about how climate change is impacting their hometowns. Listen to the students' stories here! “Climate change” wasn’t my original teaching assignment. During the 2016-2017 academic year, I was a Fulbright Scholar in the West African country of Niger, sent to teach at the national university in the capital city of Niamey and continue my research on water vendors. I am a cultural geographer and I arrived in Niamey expecting a position in the university’s expansive Geography Department. You can imagine my reaction, then, when the US Embassy in Niger re-assigned me to the West African Science Service Center for the Study of Climate Change and Land Use (WASCAL), which offers a master’s degree in Climate Change and Energy. As a geographer, climate change has been an underlying theme in almost every course I have taught, but I felt a little out of place among a group of engineers, physicists, hydrologists, mathematicians, and computer scientists studying or teaching about the topic. On the road to Boubon, a village in Western Niger, on market day. Soon after my re-assignment, the WASCAL Director asked me to teach a graduate course called “Communicating Climate Change,” essentially a public speaking course with climate change as the focus. The goal was to build and hone students’ oral skills related to climate change topics to prepare them for the multitude of audiences to whom they might speak in their careers: NGOs with grant money, academic communities, government organizations, politicians controlling policy and practice, and young people who can change practices to improve the environment. Oral presentations are not a significant part of the West African university curriculum like they are in the U.S., especially in the natural sciences, and none of my students had ever delivered a public presentation prior to my class. My students were initially a bit intimidated by the act of public speaking, but they met the challenge head on and produced very engaging and dynamic work. After receiving my new teaching assignment, my next step was to gather some resources. This proved to be challenging in a country where internet access is slow and inconsistent. I remember lamenting my access to resources on climate change (or lack thereof) in a phone conversation with my sister, and she put me in contact with Katie O’Reilly Morgan at the Wild Center in Tupper Lake, NY, my hometown. Katie recommended I check out the Climate Stories Project website. The stories I read and listened to on the sight were compelling and passionate, but I noticed that no stories from the African continent, a place with some of the most vulnerable populations in the world, were available. I was inspired to add some. A student in the Social Sciences at Abdou Moumouni University doing homework problems on one of several outdoor chalkboards. It wasn’t just Climate Stories Project that inspired me, it was my students as well. I remember the day I met Shari, a male student from Nigeria. He had notice me park my car in the empty area across from the WASCAL building and had quickly come over, offering to carry my bag. I was flattered by this offer, but also a bit uncomfortable, as it is quite unusual in the US for students to help professors carry materials. Shari might have been the first to offer, but I found this level of hospitality come from all of my students. Lawali, a male student from Niger, always made sure the technology in the classroom was working. Fatoumata, a female student from Mali, was so patient with my French. In the US, I often have to work hard to put my students at ease, but in Niger, it was the other way around. I was the outsider, yet my students went out of their way to make me feel like I was a part of their program. It was through these casual interactions, and of course during my class, that I heard their personal stories about how climate change had affected their lives and those of their families, and what inspired each of them to pursue a graduate degree in climate change science. My students’ stories add incredible diversity to an already impressive collection. The US climate change curriculum tends to emphasize the melting of polar ice caps/glaciers and sea level rise, among other effects of global warming. To my students, however, most of whom are from the Sahel region of West Africa (a mostly landlocked, semi-arid region at the edge of the Sahara Desert that gets limited seasonal rainfall), sea level rise is not a central concern. Furthermore, because the WASCAL program draws students from all over West Africa, I was able to collect stories from students from 4 different countries: two that are landlocked, two that are not. Although all the students who contributed stories to this project are all working on ways to promote sustainable energy development and reduce the impacts of climate change in their respective countries, the stories they share are all different, as the they were inspired by different circumstances and life experiences. I am grateful to ALL of my WASCAL students, those who permitted me to submit their stories to the Climate Stories Project and also those that requested my confidentiality. They deepened my understanding of climate change and its effects by selflessly sharing their experiences. I commend them for dedicating their careers to improving conditions in West African countries. Dr. Keough and her students at the WASCAL building at Abdou Moumouni University ,with special guests Malam Saguirou (Nigerien documentary filmmaker) and Halimatou Hima (Nigerien Doctoral Candidate at the University of Cambridge, UK). All photos by Sara Beth Keough

2 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed