|

It can be challenging to capture great audio for your climate interviews—I'm not a professional sound engineer and I've managed to make many mistakes over the years. I hope that sharing my errors helps you avoid these mistakes and make great audio recordings!

Mistake 1: Recording in a noisy room Admittedly, this one can be a bit hard to control: You've set up an interview only to discover what you thought would be a quiet coffee shop is much louder than you expected. Or you're recording as part of a school workshop and many other interviews are going on at the same time. If possible, try to find a quiet area to record which will not have too many distractions. Mistake 2: No microphone windscreen for outdoor interviews I've had a decent number of interviews ruined from outdoor wind noise. It's super important to use a microphone windscreen for any outdoor recordings, or even a tiny breeze will sound like a roaring gale. There are tons of different windscreen models available, even for smartphones—you don't have to spend a fortune to get a good one! Mistake 2: Having the microphone too far away from the interviewee Depending on the type of mic you're using the distance will vary, but generally it’s better to be too close rather than too far away. A mic placed too far away will have more background noise which can decrease the quality of your recording. Unless the recording gets distorted (see next mistake), it's better to place the mic close. Mistake 3: Setting the recording levels too soft or too loud Most portable recorders have a recording meter which shows the level of sound being recorded. On the far left of the meter is usually a negative number such as "-48" and to the far right of the meter is "0". Your recording level meter uses "0" to mark the point where the sound will be distorted, so you don't want to get too close to this point. But you also don't want to be too far below "-12." Set the recording level so that the signal hovers around "-12" when the interviewee is speaking at normal volume—it might take some experimentation to find a good setting. Mistake 4: Not doing a test recording You may think everything is good to go with your room setup, mic placement, and mic levels, but it's a very good idea to do a short test recording just to be sure. I've not done this and then found later that there was a problem that could have been quickly resolved. Record the speaker introducing themselves for 10 seconds, and then listen back using headphones, making changes as needed before the full interview starts. Mistake 5: Not wearing headphones during a Skype interview I recorded a few interviews over Skype which had a weird echo. What happened was that the computer recorded the speaker's voice directly and also recorded their voice coming out of my computer speakers. These two were slightly out of sync, causing the echo on the recording. Wear headphones so you don't have this problem. Mistake 6: Saying things like "right" or "exactly" while the interviewee is speaking It might be a bit unnatural to not verbally acknowledge what the speaker is saying, but you'll have a cleaner recording and less editing challenges if you let the interviewee speak without you speaking at the same time. There are other mistakes I've made but this is a good place to leave it for now! Hope this helps and happy interviewing!

6 Comments

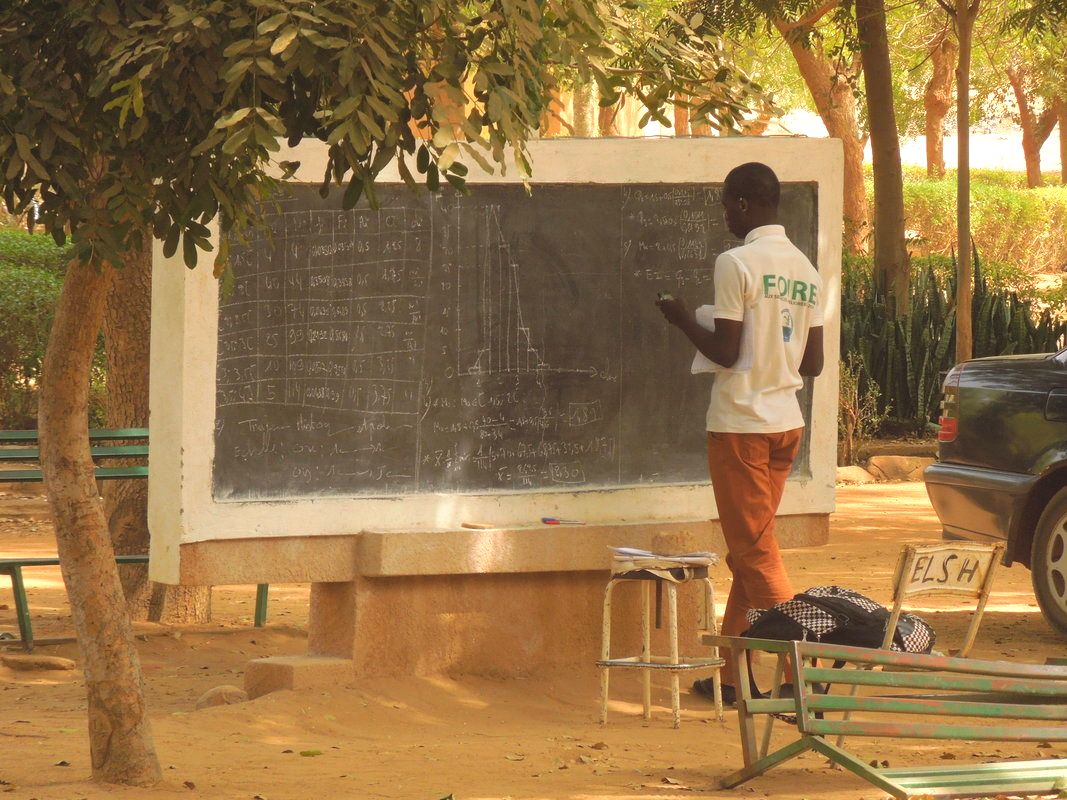

Shrinking ice fields, Mount Kilimanjaro Shrinking ice fields, Mount Kilimanjaro The following is a reflection written by Paul Smith’s College President Cathy Dove on her recent trip to Tanzania and Mount Kilimanjaro. As President of Paul Smith’s College, I have both a personal and professional interest in addressing issues dealing with the future of our planet and its inhabitants. Through the great work of the faculty and students, our college is committed to addressing climate change through education and research. One prime example of this is Paul Smith’s Climb it 4 Climate initiative, led by Bethany Garretson. This initiative is designed to raise money for student scholarships while promoting awareness of climate change issues. The more I learned about Climb it 4 Climate, it became clear that I had the unique opportunity to merge a long-standing goal of climbing one of the world’s highest peaks – Mt. Kilimanjaro – with providing support for this great initiative. Bethany was already planning to climb Aconcagua – the highest peak in South America and another of the seven summits of the world. My attempt to scale Kilimanjaro would complement her efforts. At 19,341 feet, Mt. Kilimanjaro is the highest peak in Africa. Due to its rapidly shrinking ice fields, it has been recognized as a very visible indicator of global climate change. Thus, on December 26, 2018 I began my trek up Kilimanjaro with 10 fellow climbers and over 60 guides and porters. For the next eight days we would hike through six ecological zones, beginning with a beautiful and lush rainforest and culminating in a frigid and barren Arctic zone. Along the way I had the opportunity to hear from several of the guides about how the mountain had changed since they had been leading trips. The guides were all men in their 30s who were born in the region and had been climbing the mountain for many years. In particular, the lead guide was a remarkable and thoughtful man who had been leading trips for almost ten years. He explained to me that while the rainfall in 2018 was good, for a number of years East Africa has been experiencing a lack of precipitation. So much of the Kilimanjaro region relies on the mountain – its once massive ice fields have provided abundant water to the region. These ice fields are now almost gone. Our guide estimated that in the short ten years he has been climbing Kilimanjaro they are at least 50% smaller. The troubling result is the towns and cities, with their heavy emphasis on agriculture, are struggling to maintain crop output. Dairy herds are dying. Due to increased temperatures, animals are moving up the mountain in search of food, and particularly in the Serengeti the animals are migrating further in search of water. Due to its long-standing abundance of water, the region’s infrastructure relies heavily on hydroelectric power; the lack of water has resulted in intermittent power in the towns and cities. There is widespread concern that the predicted lack of rainfall and imminent disappearance of the glaciers will result in a severe food and water shortage. Kilimanjaro guide Kibacha grew up in Moshi, Tanzania. Also, the significant tourism industry generated by Kilimanjaro adventurers would be severely threatened when the ice fields disappear. It is nearly impossible to carry sufficient water up to the highest altitudes to support the hikers; indeed currently some of the shrinking traditional water sources on the mountain have already resulted in challenges getting sufficient water up to the high altitude camps. While all of these issues are broadly acknowledged, there are no obvious long-term solutions, although individuals and the government are taking steps to anticipate dealing with further warming and lack of water, including storing food and water and regulating water utilization. These conversations with our remarkable guides were in my mind as we climbed further up the mountain. At daybreak on January 1, 2019 I reached the summit of Mt. Kilimanjaro. The bitter cold and wind did not detract from the incredible beauty and breathtaking views seen from the “Roof of Africa”. Sadly, the minimal icecaps were clear to see from the mountain peak. Those that remained were fragmented and one could almost see them cracking during the short time we were at the summit. As I descended (by far the worst part of the hike!), I reflected on the seriousness of the situation. While “Hakuna Matata” (Swahili for “no worries”) – is the Tanzanian outlook on life; it is clear that there is legitimate concern about the significant current and future impact of climate change. The Tanzanians, nor any country, can solve this problem in isolation. We each must join a unified, global community to raise awareness and create solutions. I’m proud that Paul Smith’s community is playing a leadership role in addressing one of the world’s greatest challenges. This post is by Berenice Tompkins and has been shared on her personal blog at climatefootsteps.wordpress.com. I am currently walking from Rome to the Katowice, Poland COP24 climate summit on a journey called the Climate Pilgrimage. The climate pilgrims are from seven different countries and many walks of life, and climate storytelling is an important part of our mission. We are walking both to give a human face to climate change and tell stories from our home countries, particularly climate front-lines like the Philippines, and to document and share the ways climate change is appearing in the European countries we pass through. Though climate change does not affect every place equally, it does affect every place, and it’s important that we talk about the changes we can see around us and connect the dots to help form a bigger picture. In addition to the videos we have been recording with people we meet, I want to share these story snippets from the route we’ve walked so far in Italy, Slovenia and Austria. Italian climate stories: A few days after we left Venice, the city flooded until the marathon runners were running through knee-deep water (see pictures here). Venice already floods on a regular basis – San Marco Square filled with water the day we arrived, before the storms had even started – so it’s frightening to think what a few more feet of sea level rise could mean for the city and others like it. Moving on from Venice, we pilgrims walked for three days in monsoon-like rains, with passing trucks spraying us with sideways torrents of water. Our meteorologist friend Luca Lombroso explained that the floods were caused by a Mediterranean cyclone, and that he’s never seen such an intense storm in this region in thirty years of weather forecasting. Gildo, our host in Rovigo, explained that farther south in the country, the combination of deforestation for agriculture and climate change is causing floods: it’s raining heavily much more often, and water runs off the bare soil without trees to absorb and contain it. During the period of heavy rain in late October, floods in Sicily killed three people. A friend in Ravenna described greater temperature extremes: much hotter summers and colder and snowier winters. “We never used to get this much snow in winter,” she said, “and our infrastructure isn’t prepared for it. The city can’t function.” Many homes and buildings we visited in Northeastern Italy were infested with stink bugs, which our friend Giancarlo attributed to climate change. Giancarlo also pointed out rising numbers of mosquitoes, particularly in areas of Veneto and Friuli-Venezia Giulia that are former swamps. In a community center building where we arrived to sleep outside Padova, we discovered with horror that the walls and ceiling were covered with hundreds of mosquitoes. We slept with T-shirts over our heads. Our friend Ambra, of Trieste, said she can hardly spend time outside now because her backyard is so full of mosquitoes. Public health experts are concerned that these larger populations of mosquitoes could begin to spread tropical diseases like malaria and Dengue into Europe. Slovenian and Austrian climate stories: The beech tree is the national tree of Slovenia and a very important part of Slovenia’s southern forests, but we learned from Mirko of the Forest Service that beech trees are now migrating north because their current range is becoming too warm. The spruce trees that make up forests in northern Slovenia are suffering because the insects that attack them are now able to over-winter, the same problem that afflicts hemlock trees in the United States. Flowers are still blooming in mountain areas of Slovenia and Austria, where Father Primoz says it should be snowing by now. For most of October and early November, we’ve walked in T-shirts, even when passing through high-altitude mountain areas. Our host Maria, an organic fruit farmer, tells us that for the last two years, late frosts have destroyed many of her apples and left few in good enough condition to sell. This past summer was also unusually hot, and greater temperature extremes and dryness in the summer are likely to harm agriculture in the coming years. Maria’s son is thinking of following in her footsteps as a farmer, but she is conflicted about whether to encourage him – it’s becoming more and more financially difficult to survive off a farm. More climate stories to come from Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Poland! You can follow the climate pilgrims on our Facebook page for daily updates on our progress toward Katowice. This post was written by Bethany Garretson, Environmental Studies Professor at Paul Smith's College in the Adirondack Park, New York State.  Bethany Garretson Bethany Garretson I believe in the power of storytelling. Think of all the places a story has taken you: The savannahs of Kenya, the sand dunes of Egypt, the bayous of the Mississippi delta, or the battlefields of Gettysburg. We are made of stories and these stories want to be told. I’m a professor of Environmental Studies at Paul Smith’s College, a small liberal arts school in the Adirondack Park. I’ve included an interview assignment in every class I’ve taught because I view story-listening and interviewing as one of the greatest skills for students to develop. Our stories are a part of history and I find the skill of listening to be incredibly valuable and very often overlooked. Many of the storytelling projects in my classes focus on interviewing elders, as it is vital to bring young and old generations closer together. Simple interview questions, such as Describe Your Childhood, can reveal how elders’ values and perspectives were shaped. I do not agree with the popular culture sentiment of villainizing the process of aging in America. On the contrary, older people’s lifetime of observation and experience brings wisdom. In a Haudenosaunee longhouse during the long winter months, the elders would tell stories around the fire and give them meaning for the younger generation. Today, we need to talk about the changes we’ve seen in our environment. And it is time to sit and listen to our elders. I met Jason, the director of Climate Stories Project, in 2016 at the Youth Climate Summit in Tupper Lake, New York. I’d just attempted to be the first woman to thru-hike all 46 High Peaks (mountains over 4000 feet) in the Adirondack Park without any outside assistance. It was a hike of over 200 miles with 90,000 feet of elevation change. I’d dedicated my climb to climate change awareness, dubbing it “Climb It 4 Climate.” Although I was maintaining a record pace, the temperatures soared to 95 degrees on the fifth day of the hike, and with the fear of heat exhaustion, I stopped at 132 miles and 23 mountains. At the Youth Climate Summit I spoke about human energy and the power that lies within each and every one of us. I shared the lessons I learned on the trail and from organizing a national campaign. What I found at every phase of my adventure was that human kindness is abundant and we yearn for reasons to come together and be resilient. Jason’s Climate Stories Project table at the Youth Climate Summit stood out to me because it was about sharing our own stories of the changing climate. Using his educational workshop format, my Environmental History and Social Justice Class interviewed locals and presented their stories in a short video entitled, “Adirondack Climate Stories.” Today, I’m a PhD candidate at Antioch University and I’m focusing my doctoral research on collecting climate stories from the mountainous regions of the world. In February 2019, I’m taking “Climb it 4 Climate” to Argentina. While our team hopes to reach the summit of Aconcagua, the highest mountain outside Asia, my mission is twofold. Again, I’m interested in the stories of local people about the changing climate. I plan to ask questions such as: What changes are you seeing in the mountainous environment? How have these changes impacted your livelihood? I feel it is paramount to tell these stories, as climate change is impacting mountainous regions at a faster pace than most places on earth. I am dedicating my life’s work to caring for the natural world. Today I climb, write, teach, and hope to inspire others to tell their stories. While it’s relatively easy to raise awareness about our changing climate, it’s much harder to inspire a transformation in our relationship to the planet. I know it’s ironic to travel the world to collect data on climate change, leaving a large carbon footprint behind. In the end, I hope the stories justify this harm and lead to changed behavior. Even if we cannot see past the politics of climate change, everyone wants a safe future for their children and grandchildren. So tell your own climate story, or interview someone else about theirs, and you will capture a valuable piece of history. And in the end, that may give us a greater understanding of our current reality.  If you’d like to follow or participate in Bethany’s Climb it 4 Climate campaign, you can reach out to her at [email protected] or join the Facebook group Climb it 4 Climate. By Jason Davis, director, Climate Stories Project This blog post originally appeared on the Artists and Climate Change site.  John Sinnok, Iñupiat elder, Shishmaref, Alaska. Photo by Jason Davis John Sinnok, Iñupiat elder, Shishmaref, Alaska. Photo by Jason Davis I write and perform music that features the recorded voices of people speaking about their responses to climate change. When I tell people this I normally get a response like, “That’s really interesting!” I usually relate a little of my background, as they are probably thinking “What the heck are you talking about?” For most of my adult life, I have been alternating between working as a jazz bassist and an environmental educator (with a fair amount of English as a Second Language teaching thrown in, but that’s another story). I realized I wanted to engage with environmental issues through music, but I’m not a singer, so writing lyrics about climate change wasn’t an option. For a long time, I kept my music and “environmental” work separate, but continued wondering if there was a way to combine them. I started to figure out how when I paid attention to my own responses to the changing climate. I noticed that the seasons I knew as a child growing up near Boston have changed a great deal. Winter, which used to be in full swing by Christmas, now often doesn’t get going until mid-January. Springs are shorter, and shift suddenly into 90-degree weather. The summers I remember, with gradually increasing heat and humidity swept away by dramatic thunderstorms, seem to have been replaced by long, oppressive heat waves which dissipate with barely a drop of rain. I’m sure that others are bothered by these changes as much as I am, but people (including myself) don’t discuss them very much. If you’ve ever tried to have a conversation about how the weird weather is probably caused by the changing climate, I bet it trailed off awkwardly. There are a host of reasons for this phenomenon, discussed at length by author George Marshall in his book Don’t Even Think About It. People don’t usually talk about the Holocaust either. However, musicians have found ways to help audiences access their charged emotions around this difficult topic and sometimes even talk about them. In Steve Reich’s harrowing piece, Different Trains, he integrates archive recordings of Holocaust survivors speaking about their traumatic experiences, including being transported on “different trains” to Nazi death camps. After listening to Reich’s piece, I realized that I could do something similar for the issue of climate change by integrating people’s stories of their experiences with the changing climate into original music. Maybe listeners of this music would relate to climate change in a more direct way than reading reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change or wading into the distracting political “debate”? The first step was to talk to people on the front lines. In 2015, I traveled to Shishmaref, Alaska, a village located on a small barrier island on the Chukchi Sea. Shishmaref is rapidly eroding from a combination of rising sea levels and melting sea ice, exposing the small town to the full force of winter storms. Members of this largely Iñupiat (western Inuit) community have vivid stories to tell about the ways in which climate change is destroying their home. I worked with a group of local high school students who interviewed adults, including their grandparents and parents, about the impacts of the changing climate in Shishmaref. One of the most vivid stories was told by Iñupiat elder John Sinnok, who related his intimate knowledge of the natural environment around Shishmaref, and how it is being impacted by the dramatic shifts underway. Sinnok described details that most of us would miss, including how the sound of people walking on winter snow has changed as the climate has warmed. I was touched by his very personal observations, and immediately recognized that his words could form the basis of a piece of original music. The following year I wrote and recorded John Sinnok, a piece for jazz quartet and string quartet which is built around excerpts of Sinnok’s interview. Since visiting Alaska, I began a doctorate in music at McGill University in Montreal and have started recording climate stories from around Canada. In 2017, I traveled to the Mingan Archipelago National Park Reserve in eastern Québec with a group of Montreal-based artists. There I recorded an interview with park ranger Guy Côté, who described how his childhood activities were structured around natural cycles. He related that “There was a right time to pick blueberries, there was a right time to hunt, a right time to do [all these things] …” With changes in the climate, it has become harder to predict the timing of these activities. He described how he used to tell visitors to the park that a good time to see arctic plants in bloom was late June, but now by that time most of these plants no longer have flowers. I also recorded Côté singing some traditional Acadian songs, one of which I included in a sound montage along with excerpts of his spoken narrative and environmental sounds I recorded in the park. My work making music from climate narratives has grown into a larger initiative called Climate Stories Project. In addition to recording climate narratives from people around the world, I lead educational workshops in high schools and colleges for which students interview local community members or remote interviewees via Skype about their responses to the changing climate. Lately I have come to see the various facets of my work as an inclusive artistic practice, and I am excited to help people connect with our changing environment through education, storytelling, and music. The more I do this work, the more I’m convinced that, whether or not we can “solve” climate change, we urgently need to engage with it. In this post, geography professor Sara Beth Keough of Saginaw Valley State University describes her work with West African graduate students in Niamey, Niger. During her time there as a Fulbright Scholar, she coached the students in planning and recording their stories about how climate change is impacting their hometowns. Listen to the students' stories here! “Climate change” wasn’t my original teaching assignment. During the 2016-2017 academic year, I was a Fulbright Scholar in the West African country of Niger, sent to teach at the national university in the capital city of Niamey and continue my research on water vendors. I am a cultural geographer and I arrived in Niamey expecting a position in the university’s expansive Geography Department. You can imagine my reaction, then, when the US Embassy in Niger re-assigned me to the West African Science Service Center for the Study of Climate Change and Land Use (WASCAL), which offers a master’s degree in Climate Change and Energy. As a geographer, climate change has been an underlying theme in almost every course I have taught, but I felt a little out of place among a group of engineers, physicists, hydrologists, mathematicians, and computer scientists studying or teaching about the topic. On the road to Boubon, a village in Western Niger, on market day. Soon after my re-assignment, the WASCAL Director asked me to teach a graduate course called “Communicating Climate Change,” essentially a public speaking course with climate change as the focus. The goal was to build and hone students’ oral skills related to climate change topics to prepare them for the multitude of audiences to whom they might speak in their careers: NGOs with grant money, academic communities, government organizations, politicians controlling policy and practice, and young people who can change practices to improve the environment. Oral presentations are not a significant part of the West African university curriculum like they are in the U.S., especially in the natural sciences, and none of my students had ever delivered a public presentation prior to my class. My students were initially a bit intimidated by the act of public speaking, but they met the challenge head on and produced very engaging and dynamic work. After receiving my new teaching assignment, my next step was to gather some resources. This proved to be challenging in a country where internet access is slow and inconsistent. I remember lamenting my access to resources on climate change (or lack thereof) in a phone conversation with my sister, and she put me in contact with Katie O’Reilly Morgan at the Wild Center in Tupper Lake, NY, my hometown. Katie recommended I check out the Climate Stories Project website. The stories I read and listened to on the sight were compelling and passionate, but I noticed that no stories from the African continent, a place with some of the most vulnerable populations in the world, were available. I was inspired to add some. A student in the Social Sciences at Abdou Moumouni University doing homework problems on one of several outdoor chalkboards. It wasn’t just Climate Stories Project that inspired me, it was my students as well. I remember the day I met Shari, a male student from Nigeria. He had notice me park my car in the empty area across from the WASCAL building and had quickly come over, offering to carry my bag. I was flattered by this offer, but also a bit uncomfortable, as it is quite unusual in the US for students to help professors carry materials. Shari might have been the first to offer, but I found this level of hospitality come from all of my students. Lawali, a male student from Niger, always made sure the technology in the classroom was working. Fatoumata, a female student from Mali, was so patient with my French. In the US, I often have to work hard to put my students at ease, but in Niger, it was the other way around. I was the outsider, yet my students went out of their way to make me feel like I was a part of their program. It was through these casual interactions, and of course during my class, that I heard their personal stories about how climate change had affected their lives and those of their families, and what inspired each of them to pursue a graduate degree in climate change science. My students’ stories add incredible diversity to an already impressive collection. The US climate change curriculum tends to emphasize the melting of polar ice caps/glaciers and sea level rise, among other effects of global warming. To my students, however, most of whom are from the Sahel region of West Africa (a mostly landlocked, semi-arid region at the edge of the Sahara Desert that gets limited seasonal rainfall), sea level rise is not a central concern. Furthermore, because the WASCAL program draws students from all over West Africa, I was able to collect stories from students from 4 different countries: two that are landlocked, two that are not. Although all the students who contributed stories to this project are all working on ways to promote sustainable energy development and reduce the impacts of climate change in their respective countries, the stories they share are all different, as the they were inspired by different circumstances and life experiences. I am grateful to ALL of my WASCAL students, those who permitted me to submit their stories to the Climate Stories Project and also those that requested my confidentiality. They deepened my understanding of climate change and its effects by selflessly sharing their experiences. I commend them for dedicating their careers to improving conditions in West African countries. Dr. Keough and her students at the WASCAL building at Abdou Moumouni University ,with special guests Malam Saguirou (Nigerien documentary filmmaker) and Halimatou Hima (Nigerien Doctoral Candidate at the University of Cambridge, UK). All photos by Sara Beth Keough

Youth Leading in Climate Action by Karrie Quirin “Your task as the young… is to reinvent the universe, the universe made out of stories — to change the stories, to tell them, to bury them, and to give birth to them. A difficult task, but not an impossible one.” – Rebecca Solnit With the recent news of the US withdrawing from the Paris Accord, many young people are feeling overwhelmed and distraught. However, I wanted to speak to young people today and let them know that hope is not lost. In fact, now is the most important time to take action —and many young people like myself are doing so. To other inspire others, I want to share a few of my personal actions against the climate crisis. Two groups I am working are doing amazing work. My involvement with SustainUS is through their COP23 Creative Challenge, which gives young people (ages 18-25) the chance to become a youth delegate at the COP23 (Conference of Parties) in Bonn, Germany in November 2017. The Creative Challenge asks youth to submit artistic work, such as a painting, blog, or song that expresses their passion for climate justice. Through two rounds of competition, participants tell their personal story and emphasize the importance of taking action. This opportunity is amazing because it puts youth in the forefront of the climate movement and allows their voices to be heard on the world stage. For the Creative Challenge, I told my personal story about climate change through Climate Stories Project, and also submitted this poem: Patient Name: Mother Earth I’m checking for Her vital signs and they are fading. A fact we’ve known for decades but still are waiting… Waiting for the forests to regrow. Waiting for the seas to retreat. Waiting for the carbon levels to slow. Waiting for water in this heat. Waiting and waiting and yet still debating- If we are the cause or if it’s just how the earth works. Let me ask you- Do you blame the victim of an assault? “She looked too appealing so it’s her fault” But I guess that’s not considered rape Even when you claim Her as your own landscape? Or should she be considered abused? If you take and take Until every single last resource is used But, if this goes unseen is the behavior excused? - - - - - - -- -- -- - -- - - - - - - So often we turn a blind eye to those who need us most. In Her case, like many, the case cannot be easily Diagnosed. The cure is a challenge. That will take years to perfect The cure is a battle. But for Her we shall fight to protect. For She was never or ever will be merely an object. The audio recording of my poem can be heard here. You can see all the submissions from the Creative Challenge here. Another group I am working with is Earth Guardians. Starting this past April, I became a member of Earth Guardian’s RYSE Youth Council, which stands for Rising Youth for a Sustainable Earth. We are a group of 21 young environmental leaders in our local communities. We work together to support each other and promote national efforts to advance sustainability—a top priority is fostering new youth leaders for climate action. One way we are going to do this is through a summer training for which we will learn communication and leadership skills, which we will then put to use in our own communities. To make this happen, we are have a fundraising campaign which lasts until June 30th. We kindly ask for your support! I sincerely hope that my experiences inspire other youth to take action against climate change. There are so many ways to get involved and make a difference. The future of our planet is in our hands!

By Berenice Tompkins

This past Thanksgiving, I visited family in Western North Carolina. My grandmother’s home is in Saluda, a tiny town close to the South Carolina border and a little ways east of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which straddles North Carolina and Tennessee. My great grandfather ran a camp in this area, and my dad and his brothers spent their summers there, exploring the green, wet Blue Ridge Mountains. I started traveling down alone to stay with my grandmother in the Saluda house when I was four, and her back porch, overlooking the mountains and some of the world’s greatest sunsets, remains one of my favorite places in the world. For a good part of this visit, however, neither mountains nor sunset were visible. The smog extended to the trees lining my grandmother’s yard, about 100 feet in front of the porch. The air smelled half like a campfire and half like burning plastic, presumably from the manmade debris caught in over thirty wildfires that had been burning in North Carolina, Georgia and Tennessee for the past month. We first heard about them through a second cousin, a chef at a lodge that evacuated completely when the fire started pouring down the mountain directly across the lake. He also told us that much of Sevier County, Tennessee, childhood home of Dolly Parton and site of the amusement park Dollywood, had burned down. What’s most worrying about these fires is that the Blue Ridge and Smoky Mountains area is a temperate rainforest – it’s known for being cool, damp and rainy even in the summer months. The fires followed two months without rain and a year of drought, as well as the third warmest October since 1963 and second warmest January-October period in the last 122 years, according to the NOAA. It’s believed that the majority of the fires were manmade – it can be easy for a hiker to drop a cigarette and start a huge blaze when conditions are this dry. The Sevier County fire, which was reportedly started by teenagers, killed fourteen people, injured 191, damaged or destroyed over two thousand structures and forced over 14,000 people to evacuate. The mayor of Gatlinburg referred to it as a “fire for the history books.” Our area of North Carolina was not impacted as drastically, but the fires severely affected air quality. When the wind blew the smoke toward the house, the air smelled so toxic we had to keep all the windows closed. Each morning I coughed up globs of yellow gunk. We weren’t even in the towns closest to the large fires, where it must have been very difficult to breathe. Since we couldn’t be outside on several days, I took the opportunity to do some Climate Stories Project reporting and talk to friends about what was going on. I interviewed Chris Price, a family friend, homestead farmer and naturalist, about his experience of the wildfires, as well as other ways he’s observing climate change in the area and on his farm. Listen to Chris’ story below. I also spoke with my friend Steven Norris, a climate justice organizer, who reminded me of what had been happening on the other side of the state – while western North Carolina was crying out for water, the eastern coast was being drenched by Hurricane Matthew. In addition to organizing to support for communities affected by Matthew, Steve is also organizing to stop a piece of natural gas infrastructure bound to exacerbate climate catastrophes like these ones – the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. Steve recently helped organize the Walk to Protect Our People and the places We Live, a along the proposed route of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. I’ll be posting his interview soon, including a reflection on that experience. Update: The Southern Appalachian wildfires aren’t the only ones wreaking destruction around the world this year. Read here about the wildfires currently afflicting Chile.

By Berenice Tompkins

Since I began collecting climate stories, I’ve started to notice them everywhere I go. I visited family in England this past Christmas and got to travel to parts of the country I'd never seen before. In each region we visited, we heard climate stories. When my uncle returned from visiting friends in Sussex, southern England for New Year's, he reported that they have decided to turn their property into a champagne vineyard after learning that the region’s climate has become similar to that of Champagne, France two hundred years ago. My mother and I visited my great aunt and uncle in Sheffield, in the north, and got into a conversation about the winter weather. My great aunt mentioned that it wasn’t nearly what it used to be – several decades ago, they’d spend the winters shoveling piles of snow. The past few winters, there have been infrequent sprinklings of snow, never enough to shovel. We headed further north to the Lake District to visit my cousin's girlfriend's family for the first time, and they told us that severe floods last year destroyed a bridge that had just celebrated its 200th anniversary. Toward the end of our trip, I went to see a friend in Cambridge, and he fondly recollected ice skating as a child on the area’s fens, or marshes, which used to freeze through each winter. Now, he said, they’re no longer frozen consistently enough for kids to skate safely. Below is a map of England, with pins placed on the areas mentioned. I am always surprised by the diversity of ways climate change appears in different places. The more I do this work, the more I see that climate change is showing up everywhere.

Click to set custom HTML

By Jason Davis

Remember when most news stories about climate change included a sentence like, “By 2050, scientists predict that a global temperature rise of 2 degrees will cause a large range of disruptions to the earth system”? Well, it’s 2017 and many of these disruptions, such as a drastic reduction of Arctic sea ice, record-breaking Australian temperatures, and extreme flooding in California, are happening decades ahead of schedule. However, it’s not always clear when we can link unusual weather and unexpected changes in our environment to climate change. For example, how do we know when a freak ice storm in May is influenced by global warming? The work of climate scientists has allowed us to more confidently tie our observations of unusual weather to climate change. Until recently, scientists did not have sufficient data to conclusively link a weather event, such as a severe drought or an unusually strong hurricane, to global warming. In the past, news stories about huge calving icebergs or massive forest fires often included a statement by a scientist stating that there was “no evidence” that climate change played a role in the event. However, in recent years scientists have become more adept at detecting the “fingerprint” of climate change, following concerted efforts to determine if individual weather events can be attributed to global warming. To grossly oversimplify, scientists have harnessed enormous computing power to establish the likelihood of an severe hurricane or drought not occurring without human-caused elevation of greenhouse gas levels. In many cases, they have concluded that the current intensity of many weather events would be extremely unlikely without elevated greenhouse gas levels. In other words, equipped with reams of data, scientists are increasingly confident that these events are exacerbated by human-caused climate change. Just as scientists are becoming more confident in their attribution of extreme weather events to climate change, the rest of us are becoming more certain that our own experiences of our changing local environments are linked to these global trends. As we increasingly share our observations of how the weather is "getting weirder" in our communities, we build a worldwide network of climate change stories. We gather more and more “data” in the form of these stories, and become increasingly convinced that our individual experiences are evidence of global change. In this way, we do human-scale climate change research, using the scientific evidence to bolster our own observations, rather than simply showing real-world manifestations of change expected from climate change models. Some may balk at this approach, arguing that it is impossible to use “anecdotal” evidence to attribute extreme weather events to climate change. Critics rightly point out that climate change deniers have taken a similar tack to "disprove" global warming, for example by claiming that an unusually cold winter in Washington D.C. demonstrates that climate change is just a hoax. We should be wary of, for example, blaming climate change for an isolated warm day in January. A much more effective approach is to recognize that, for example, this year there were 15 unusually warm days in January, compared with two or three 10 years ago. In addition, if you live in New York, speak with people in Toronto (or Stockholm, Moscow, or Tokyo) about the number of unusually warm days they observed in January. Many people are convinced about the urgency of climate change based on scientific findings and models alone. However, many others are not. The rapidly growing network of climate stories quite literally brings global warming “down to earth.” Sharing these stories is perhaps the most effective way to engage people around the world with this planet-wide crisis. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed